There is a long history of feathers in fashion, as they add color, texture, and flair to bodices, shoulders, or hems. It’s hard to imagine them on everyday clothing, but for costumes or for expressing wild creative visions they’re extremely eye-catching and appealing. The dress above was designed by Yves Saint Laurent for dancer Zizi Jeanmaire. Another case of feathers in fashion: another Yves Saint Laurent design (below) from the collection of the Met’s Costume Institute, which seems to be made entirely of feathers, though it also consists of silk.

Saint Laurent also used ostrich feathers, which adorn this gloriously extravagant cape that he made for Zizi Jeanmaire. Over the years, he designed many costumes for Zizi, who was his close friend.

“Aigrettes” and Egrets

While translating Laurence Benaïm’s biography Yves Saint Laurent (forthcoming in 2019), I came across lots of specific fashion terms that required a good bit of research (I blogged about this previously here). One of these was “aigrette,” which refers to a single feather or small group of plumes used as ornamentation, usually on a hat. This word is etymologically the same as the French word for “egret,” because, traditionally, the egret’s delicate, showy feathers were used for such decorations.

This is a true “aigrette hair ornament” from 1894, featuring diamonds and the feathers of a snowy or great egret, which was shown this summer at the New-York Historical Society as part of an exhibition called Feathers: Fashion and the Fight for Wildlife.

The Environmental Cost of Feathers in Fashion

When the craze for feathers in fashion, especially on hats, exploded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many Americans grew concerned that bird populations were being decimated. In 1918, Congress passed the Migratory Bird Act, which regulated the commercial use of feathers in the U.S., leaving milliners scrambling to find new ways of ornamenting hats. America was on the cutting edge of environmental protection, as England and Europe still permitted the use of feathers from migratory birds.

A New York Times article from the period proclaimed: “Our Plumage Law to Create a Style.” The journalist described how wealthy American women in London were having the illegal aigrettes stripped from their hats and storing them in the British capital before returning home. They would then re-trim their hats in the U.S., and, upon their next trip to London, have the forbidden feathers put on once more. A London milliner claimed to know “American women who have $500 or $1,000 worth of aigrettes stored in London at the present time, in some cases even more.” The law evidently gave quite a boost to the hat-making economies of both New York and London!

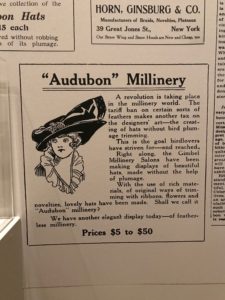

American milliners spun straw into gold, creating a market for the new featherless hats and declaring that feathers could be replaced with “rich materials…ribbons, flowers, and novelties.”

The new featherless hats were often called “Audubonnets” in honor of John James Audubon, the illustrator and conservationist.

Some of the bird-inspired hats of the past were excessive and seem quite creepy today. It’s hard to imagine wearing something like the hat below. I counted no fewer than 7 dead birds on this thing.

Protecting Birds Today

Fifteen European countries signed an international agreement on protecting birds in Paris in 1950. So, during Yves Saint Laurent’s day, there was no longer a free-for-all regarding obtaining birds’ feathers, and I don’t believe he ever used egret feathers. I’m not sure how exotic feathers such as bird-of-paradise were regulated. Ostrich farms had been established by the colonial powers in Africa as early as the 19th century, so presumably farmed ostriches were a sustainable source of feathers and remain so today. Yves Saint Laurent also used rooster feathers, which could be sourced within France without threatening any species. Birds-of-paradise are native to New Guinea, and today, according to Wikipedia, the greatest threat to the species is habitat destruction due to deforestation.