A leading translation theorist, Lawrence Venuti, talks about “domestication” versus “foreignization” when translating fiction. “Domestication” means making the foreign familiar, and Venuti rails against it. In fact, many aspects of the text—references, syntax, expressions—need to be made familiar so that the reader will not be confused or alienated, but that’s a topic for another post.

I think Venuti’s binary distinction is oversimplified. Translators do not engage in a process where they “foreignize,” i.e., make something foreign. What we can do is let the text be foreign—let it be itself. When I’m translating fiction, I often remind myself to “let the strangeness in”—to find a way to let unusual descriptions or structure remain while translating into English. The Booker Award-winning translator Jennifer Croft uses the term “microsuspense” to describe the fact that, when we read, we “experience a world in order, not all at once.” When the translator can bring across the sentence structure of the original, the target-language reader will experience the same kind of impact created by the word order.

In fact, many narrative styles can be strange, not just translated ones. When shaping a narrative, editors need to remember to let it be its own thing. Hollywood and Big Publishing may want everything to be a remix of what’s come before, but in my experience readers want the excitement of reading something they’ve never seen before.

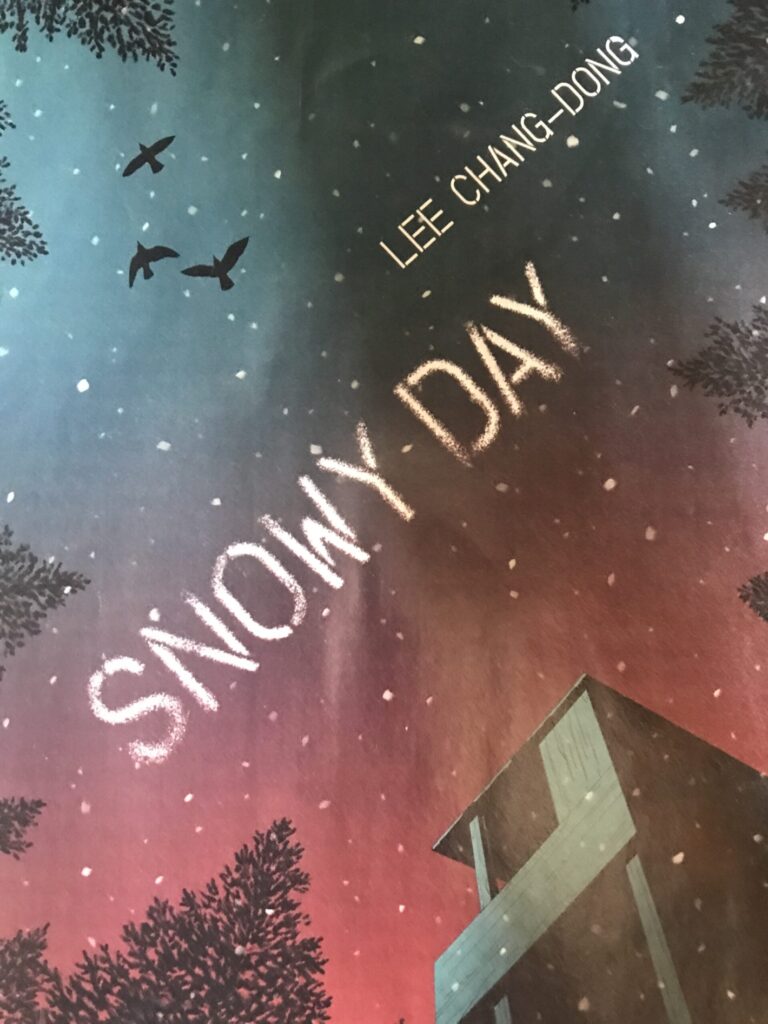

A perfect example of this is the story “Snowy Day” by Lee Chang-Dong, translated from the Korean by Heinz Insu Fenkl and Yoosup Chang, and published in the March 6, 2023 issue of The New Yorker. From its very first lines, this story takes us to an unexpected and unfamiliar world. A young woman has just walked up to a guard post in the snow and asked to visit Private Kim Young-min. The winter landscape and the military setting are foreboding, and the woman seems out of place. “The whole way up there, she’d worried that she would miss the snow.” We won’t understand what this sentence means until later in the story.

This opening is in the past tense. Soon the scene changes to the present tense, and describes a soldier. What’s the relationship between the two scenes? Does the scene with the soldier take place earlier, at the same time, or later than the one with the woman? Is this soldier the same one the woman is looking for?

As readers, we’re swimming in uncertainty, but we trust the author because the writing is so forceful and captivating:

Beside the guardhouse, with its label designating the post number, stood large signs with slogans like “Crush Them from the Start!” and “Exterminate Communism!” She noticed long rolls of barbed wire strung along the perimeter of the base, the distant barracks, the vast, snow-covered parade ground pierced by cold sunbeams. Everything seemed wrapped in a blanket of stillness. But for some reason she felt in danger, as if she were standing on ice that was about to crack, and her entire body shook with this unknowable fear.

As soon as I started reading this story, I knew I’d never read anything quite like it before. I also had the feeling it had been translated—and not just because the writer and the characters had Korean names. The way the story unfolds, the sorts of telling details that the author focuses on, the shifts from specific observations to dramatic descriptions of inner states of being—all this seems to arise from a different way of seeing the world. The English translation is beautiful, natural, and expressive, with vividly realistic dialogue; it’s the perception behind the language that feels different. Expressing this perception of the world is a vital part of the translator’s task, and a compelling reason to read fiction in translation.

Top image by Jaymantri via Pexels; middle image: illustration by Anuj Shrestha (photo Kate Deimling); bottom image by Jakob Jin via Pexels.